Illustrations

of fossils go back at least to the Renaissance, if not further. However, reconstructing

those fossils as they may have been in life, the thing we generally refer to as

paleoart, is a relatively recent practice.

Fig. 1.: Duria Antiquior - A more Ancient Dorset, 1830. Take notice of the defecating animals.

Often

regarded as the very first piece of paleoart that tried to show fossil animals

as they may have been in the flesh is Duria Antiquior - A more Ancient Dorset,

by Henry De la Beche, from the year 1830. De la Beche’s watercolour portrays the

Jurassic ecosystem that has been uncovered over the years by his friend Mary

Anning, showing the different kinds of marine reptiles all interacting with

each other (mostly through violence) in their natural environment. The piece

was made to be sold to academic institutions as a teaching instrument, the

money going to Anning, who had unfortunately fallen on hard times (Davidson 2008).

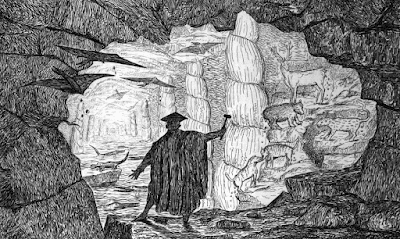

Fig. 2.: A Coprolitic Vision, 1829, proving that humour has not changed much over the centuries.

But is this

really the first piece of paleoart, in the sense of depicting fossil organisms

as living beings? No, at best Duria Antiquior was the first

one used in an academic/scientific context. What some people may not know is

that Henry De la Beche was also a passionate caricaturist and one year prior he

had created quite a daft piece titled A Coprolitic Vision. What it

depicts is William Buckland, in full academic attire and geologist’s hammer in

hand, at the entry of a cave, where he sees living prehistoric mammals, flying pterosaurs

and marine reptiles… just defecating all over the place. The cave itself looks

like the inside of a digestive tract, with the pillars holding it up resembling,

well… you know. What this was meant to satirize was Buckland’s then current

obsession with coprolites (fossilized feces), which resulted in multiple works

on the matter. This itself has had a large influence on Duria Antiquior.

If you look closely at that later painting, you can also see various animals,

especially the ichthyosaur in the foreground and the plesiosaur in the centre,

dropping logs into the water. In his recent book Ancient Sea Reptiles,

Darren Naish claimed that this was supposed to show an instinctual fear response,

but it seems far more likely that this is a nod to both A Coprolitic Vision as well as the fact that De la Beche had used

Buckland’s work on coprolites as a basis for speculating what the foodweb in

ancient Dorset may have been like, helping him determine which animals in the

painting should feed on the others.

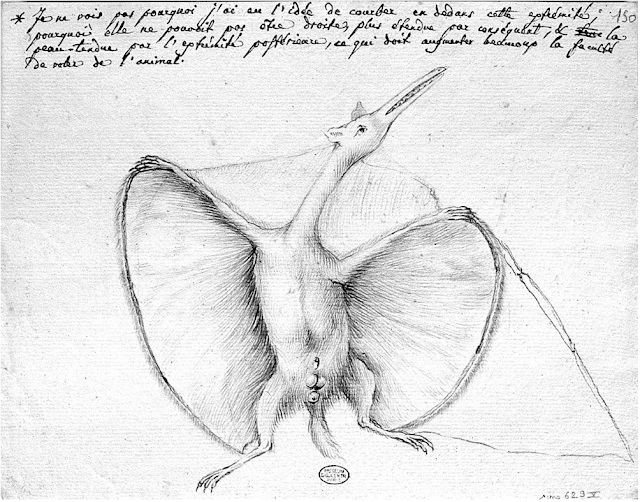

Fig. 3.: William Buckland sticking his head into a not-quite-extinct Kirkdale Cave, 1822.

So, is A Coprolitic Vision the oldest piece of paleoart then?

It may very well be the very first life reconstruction of Mesozoic marine

reptiles, but not of prehistoric animals in general. We can go back a lot

farther to find that. In 1822, for example, William Conybeare produced another satirical

piece, which again shows William

Buckland exploring a cave (De la Beche may have been deliberately riffing on Conybeare). This time it is the real life Kirkdale Cave in North

Yorkshire, where he is greeted by a group of cave hyenas. The cave was

originally a big mystery, due to containing the bones of a wide variety of

animals, such as elephants, hippos, rhinos, hyenas and bison, which (it was

thought) were not native to Britain. Buckland first analysed the cave under the

belief that the bones were remains from the deluge, having been swept into the

cave by the great flood from elsewhere on Earth. But as time went on, he

realized that the cave never had an open roof and that its only entrance was

too small to have fit in the whole bodies of most of the animals found in it.

Then he discovered that most of the bones had bite marks that fit the teeth of

the hyenas at the site. A suspicion grew, which was further supported by

Buckland finding objects in the cave that looked to him like petrified hyena droppings.

To confirm that this is indeed what it is, he went as far as comparing the

coprolites with the dung of living hyenas that he observed in British

menageries. Thus, it became obvious that all the remains at the Kirkdale Cave

were not swept in by the deluge but came from animals that had actually lived

close to it and were dragged into the cave by a hyena pack that inhabited it.

Rather than mocking him, Conybeare’s drawing is meant to celebrate this

discovery, as Buckland's study was the first reconstruction of an ecosystem from deep time.

Aided again by coprolites. One may question though if Conybeare’s drawing would

have actually counted as the restoration of an extinct animal at the time he made it, as it was only just

then being debated if the European hyena bones in question were from the extant

spotted hyena or belonged to a separate, extinct taxon. In that light, depending on his view, he may or may not not have been illustrating an animal he regarded as extinct, but rather one he

thought was still alive but has just lost its former range (which would be true

from a certain point of view, as the cave hyena is today regarded as simply a sub-species of the spotted hyena).

Fig. 4.: A mammoth mistake, 1805.

Going even

further back, we come across Roman Boltunov’s reconstruction of a frozen

mammoth carcass that Ossip Shumachov had discovered in the delta of the river

Lena in the year 1805. As is evident, he was apparently unaware that Georges

Cuvier had already determined by this time, based off the few fragmentary

mammoth bones that had made their way into Western Europe, that this animal was

a distinct species of elephant. Instead, Boltunov shows it as some kind of

giant… boar? Maybe? It is certainly quite an odd-looking construct. Boltunov was neither

an illustrator nor a paleontologist, but an ivory merchant, so the purpose of this

drawing was first and foremost advertisement, transmitted through private

communications between him and his contacts in St. Petersburg. He had bought

the carcass' tusks off Shumachov and was looking to sell them further, which

is how Michael Friedrich Adams got to know about the find (which is now named

the Adams mammoth). Adams was able to buy the tusks off Boltunov and also

retrieve the rest of the skeleton, including its frozen skin and other soft

bits, which were all assembled together in the Zoological Museum of St.

Petersburg.

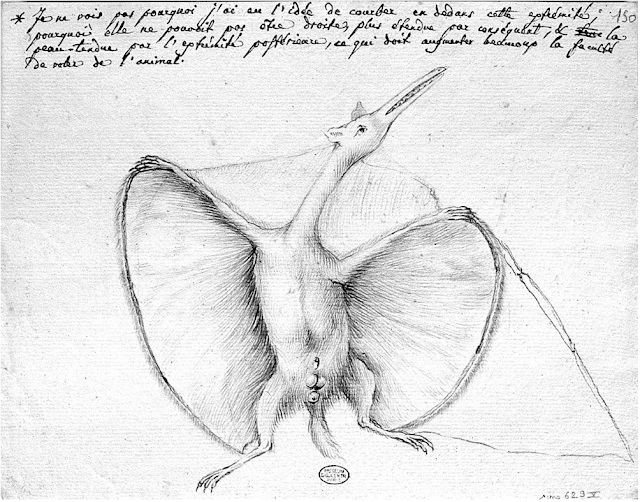

Fig. 5.: Johann/Jean Hermann's mammalian pterosaur, giving the viewer a full-frontal assault, 1800.

The

absolutely oldest known, incontrovertible piece of art that tried to depict a

fossil how it would have looked in the flesh comes from Johann Hermann (Witton

2018). This drawing from the year 1800 depicts his interpretation of the

Bavarian fossil Pterodactylus,

interpreting it as a flying mammal, which, if you have been a long-time reader,

you will know was a

popular idea among Central European paleontologists at the time. He shows

it with fur, cute ears and external genitals similar to a bat, while faint

lines indicate where he thought additional membranes may have attached or how

the wing may have moved. This was sent in private along with his writings on

the fossil to Georges Cuvier and was apparently never meant for official

publication. In fact, only in 2004 was it rediscovered that this drawing even

existed.

So, what we

can say in the end is that while the first piece of paleoart in history was not

a shitpost, if we consider that the very first one was never published for over two centuries,

the second one was an odd curiosity among Siberian ivory merchants and the

third one just showed quite modern animals, De la Beche's coprolitepost could very well have

been many people’s first introduction to restored animals from deep time. The

backstories of the two caricatures discussed here are also a testament to the influence that the

study of coprolites has had on the history of early paleontology and paleoart,

the effect still being felt right up to Duria Antiquior.

I think

most of us can also agree that Hermann’s Pterodactylus and Butanov’s

mammoth have a certain shitpost energy to them.

If you

liked this and other articles, please consider supporting me on Patreon. I am

thankful for any amount, even if it is just 1$, as it will help me at

dedicating more time to this blog and related projects. Patrons also gain early

access to the draft-versions of these posts.

Related Posts:

References:

- Davidson,

Jane: A History of Paleontology Illustration, Bloomington 2008.

-

Pemberton,

George; Mccrea, Richard; Gingras, Murray; Sarjeant, William: History of

Ichnology. The Correspondence Between the Reverend Henry Duncan and the

Reverend William Buckland and the Discovery of the First Vertebrate Footprints,

in: Historical Biology, 2008, 15, p. 5 – 18.

-

Rudwick,

Martin: Bursting the Limits of Time. The Reconstruction of Geohistory in the

Age of Revolution, Chicago 2005.

-

Taquet, Phillipe;

Padian, Kevin: The earliest known restoration of a pterosaur and the

philosophical origins of Cuvier’s Ossemens Fossiles, in Comptes Rendus Palevol,

2004, 3, p. 157 – 175.

-

Witton,

Mark: The Paleoartist's Handbook. Recreating prehistoric animals in art,

Marlborough 2018.

Image

Sources: